The F-35 engine is practically invisible to radar.

There’s a common saying around here: We don’t make the F-35 – we just make the important parts.

Of course, that’s an exaggeration. The airframe, for example, is obviously pretty important to the F-35’s ability to fly undetected by enemy radar, and we don’t make that. And there is a vast network of companies that make many of the plane’s systems, subsystems and parts. But there’s some truth in the statement too: Every time the F-35 does something, there’s a good chance an RTX product played a part.

Pratt & Whitney builds its engine. Collins Aerospace makes the visor that shows pilots what’s happening in the skies around them. Raytheon makes the precision weapons it uses for air-to-air combat and air-to-ground strikes, and the navigation system that helps it land on aircraft carriers and austere airfields.

Pratt & Whitney makes jet aircraft engines for commercial and military planes, including the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Before we get into the parts, let’s talk about the plane. It has an enormous job to do.

The U.S. military is counting on the F-35 to replace several fighters including the Air Force’s F-16s, the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ F/A-18s, the Marines’ AV-8B Harriers and the UK Harrier GR7s and Sea Harriers. That means it has to excel at air-to-air combat, carry out air-to-ground precision strikes in all weather, fly stealthily into contested areas, have unsurpassed “situational awareness,” or data on what’s going on around it, and land basically wherever the military needs it to land. And it needs to be “survivable,” a military term meaning it can either avoid or withstand attack.

“The Air Force is really buying it to be the workhorse of its fighter community. The Navy is doing the same,” said retired U.S. Air Force Maj. Gen. Jon Norman, who leads Air Power Requirements and Capabilities for Raytheon.

The U.S. expects to fly the F-35 well into the 21st century, and other nations have placed their bets on it as well. The armed services of the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Netherlands, Australia, Norway, Denmark, Finland, Canada, Israel, Japan, South Korea, Poland and Belgium all fly the fighter or have plans to do so.

The F-35 engine is practically invisible to radar.

An F-35 pilot can see in any direction at any time.

The F-35 can defeat enemy aircraft without ever being detected.

JPALS allows naval commanders to launch the F-35 in all types of conditions.

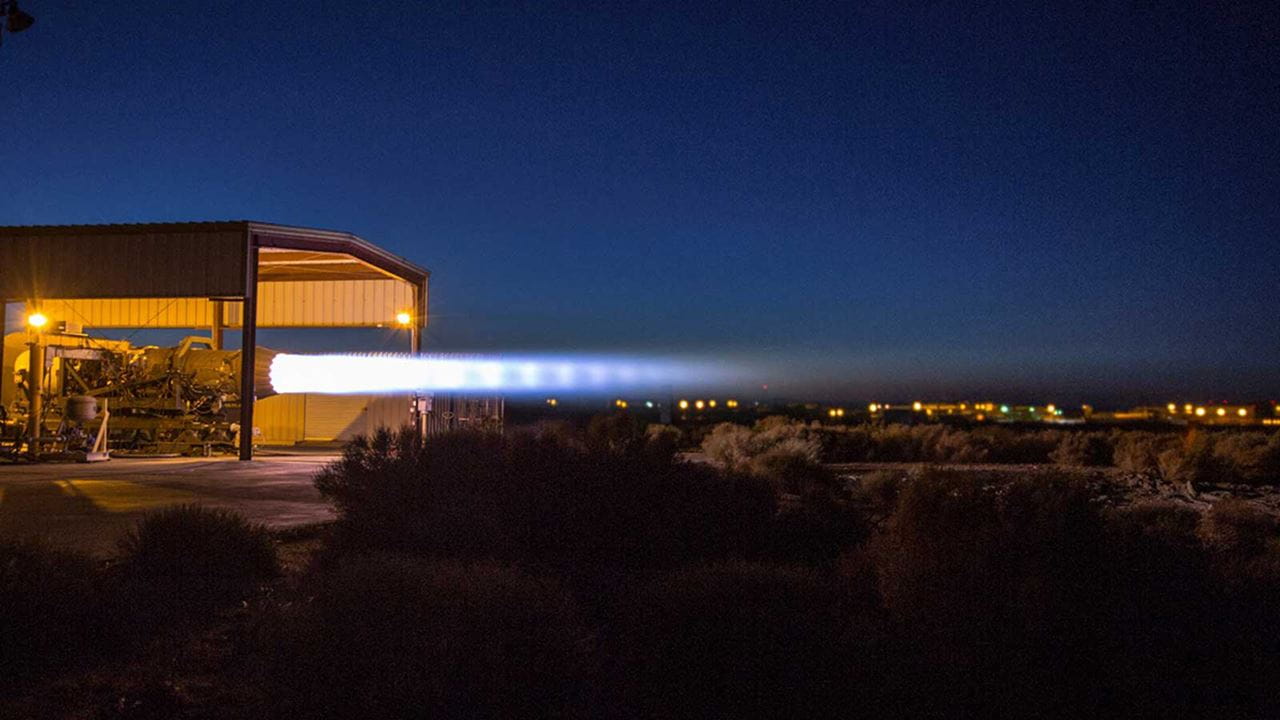

A Pratt & Whitney F135 engine performs at high-power engine run during a test at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

Since its first flight in 2006, the F-35 has been getting its thrust and most of its electric power from one place: The Pratt & Whitney F135 engine.

The F-35 is still early in its service life, but the U.S. Department of Defense is working on a fourth round of upgrades to ensure the fighter jet keeps its advantage over adversaries and remains relevant as newer aircraft take flight. That effort, known as Block 4, would push the F135 – still flying in its original configuration – far beyond its specifications.

To meet the F-35’s needs for Block 4 and beyond, Pratt & Whitney has developed the Engine Core Upgrade, an update to the F135’s power module.

Pratt & Whitney has developed an upgrade to the F135 engine as part of a plan to modernize the F-35. The upgrade has several advantages, including:

an architecture that has logged more than 1 million safe flight hours

compatibility with all three F-35 variants

Tens of billions in projected cost savings over the life of the program

meaningful capability by 2030

In addition to those benefits, Pratt & Whitney experts point to the F135’s reliability – it has logged more than 600,000 safe flight hours – along with its mature supply chain and maintenance infrastructure. The Engine Core Upgrade is also a “drop-in” solution, meaning it requires no airframe modifications.

Upgrading the engine, as opposed to integrating a completely new one, would result in about $40 billion in savings – and put a fleet of fully enabled Block 4 F-35s in the air years sooner.

The Engine Core Upgrade “is the only solution that will field fast enough, in meaningful quantities, to make a difference to the warfighter,” said Jennifer Latka, Pratt & Whitney’s vice president for the F135 program. “From a taxpayer perspective, an upgrade to the existing engine costs a fraction of a brand-new engine. And that's both near term and long term.”

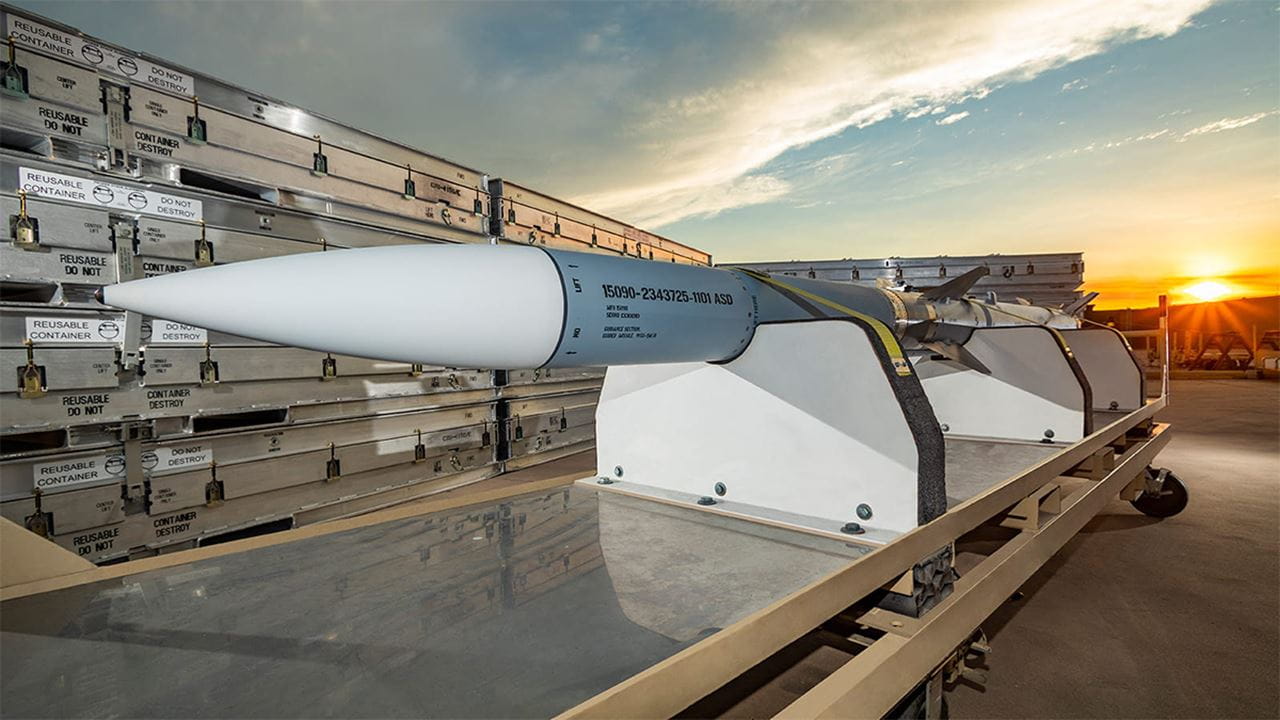

Procured by dozens of countries, the combat-proven AMRAAM air-to-air missile has been operational and integrated into the F-35, along with the F-16, F-15, F/A-18, F-22, Typhoon, Gripen, Tornado and Harrier.

One main part of the F-35’s mission is to conduct operations in hostile territory, or what military officials call an anti-access airspace denial environment, and survive whatever surface-to-air missiles or air-to-air missiles might await it. That requires stealth – the F-35 even carries its weapons internally to preserve its stealth advantage – and the ability to defeat adversaries beyond visual range. And that’s where the AMRAAM missile comes in.

A pilot flying an AMRAAM-equipped F-35 can detect, target and engage enemy aircraft at distances well beyond visual range. The missile has a semi-active radar that allows pilots to engage enemy aircraft at extreme ranges and get away before they are threatened – an advantage known as “launch and leave capability.” That, coupled with the plane’s stealthy features and advanced sensor suite, means the F-35 can defeat enemy aircraft without ever being detected.

An upgrade called F3R, or Form, Fit Function Refresh, will bring even more capability to the missile through increased range and enhanced performance against advanced threats. The U.S. Air Force has awarded Raytheon a $1.15 billion contract for the missile’s latest configuration.

“The F-35 paired with the AMRAAM preserves our first-launch opportunity against advanced threats,” Norman said. “Before they even have a track on our aircraft, our F-35 pilots are able to engage an adversary with AMRAAM and leave. This is the exact advantage our pilots need in combat and the exact capability the AMRAAM delivers.”

Another of the F-35’s missiles is the Raytheon AIM-9X Sidewinder, a shorter-range air-to-air missile that uses infrared instead of radar to detect, track and guide to a target. That helps the plane stay stealthy; fighter jets typically can sense when they’re being targeted by radar, and when they do, they alert their pilots. But with infrared targeting, there’s no such warning.

“As a fighter, if I can passively track and target and not give an adversary warning I’m there, and still employ ordnance, then I have a significant offensive advantage,” said Norman, a former F-16 pilot.

As for ground strikes, the F-35 will carry the StormBreaker smart weapon, a gliding munition with a seeker that works three different ways – millimeter-wave, which allows it to find targets in darkness and in any weather; infrared, which helps discriminate between targets, and semi-active laser, meaning it will follow the direction of a laser designator operated either from the air or on the ground.

StormBreaker is the U.S. Air Force’s first network-enabled weapon, meaning control can be transferred after launch to another fighter jet or to ground forces, which can then provide new targeting data in real time. It also has greater range than older munitions – about 40 miles – meaning an F-35 can zoom out, take a wide field of view and engage several targets at the same time.

The fighter jet also carries the Paveway laser-guided bomb, an air-to-ground precision guided munition that fulfills another of the F-35’s missions: close air support for ground forces.

One other key to the F-35’s strike capability: sometimes, it doesn’t even launch anything. The plane’s suite of radar, sensors and targeting systems essentially make it a flying sensor and battle manager, and it has even shown in tests that it can provide targeting data and guide a ground-launched missile against threats over the horizon.

These helmet-mounted displays, made through a joint venture between Collins Aerospace and Elbit Systems of America, help F-35 pilots understand the airspace around them.

One big difference between the F-35 and the planes it’s replacing is the way pilots see data from radars, targeting systems and other sensors.

Historically, fighter jets have used a head-up display – a clear piece of glass atop the instrument panel with a projector that overlays information about whatever is in front of it. With that, pilots can tell all kinds of things about their mission, including where the nose of the plane is pointing, how far away a target or waypoint is and which weapons are available.

With the F-35, the head-up display is integrated into the visor of the pilot’s helmet. The information is no longer available in only one place; it moves with the pilot’s gaze.

“You have it right there in front of you, regardless of where you’re looking – out the window, over your shoulder, down – you’re looking through the aircraft, so to speak,” said Bret Tinkey, who manages helmet programs at Collins Aerospace. “It’s all in front of you, all the time.”

Feeding into that display is one of the F-35’s most important and most revolutionary features: the network of sensors spread out across its airframe. Those sensors, called the Electro-Optical Distributed Aperture System, allow an F-35 pilot to see in any direction at any time – a major improvement over the fixed sensors on older fighters.

“The way it’s been classically, you’re frequently maneuvering your jet to receive full defensive threat coverage. Or you have a formation and one of you concentrates on one sector, while the other aircraft concentrates on another,” said Russ “Rudder” Smith, a retired U.S. Air Force colonel who now leads business development for tactical electro-optical and infrared systems at Raytheon. “With 360-degree awareness, it obviates the need for maneuvering your aircraft or formation to see the entire operating picture. You can do it all through one system.”

The sensors use two key components: strained-layer super-lattice detector material and focal plane arrays. Those advancements, coupled with digital pixel technology and a digital read-out integrated circuit, give pilots a quick, high-definition picture of everything around them, Smith said – “in short, a more capable missile detection system.”

An F-35-B Lightning II assigned to marine Fighter Attack Squadron (VFMA) 121 takes off from the amphibious assault ship USS Wasp (LHD 1). Photo by Mass Communications Specialist 1st Class Daniel Barker/Released.

Let’s go back to one of the F-35’s most important requirements: The military needs it to be a “low-observable” aircraft, meaning it has to be very hard for adversaries to detect. Doing that in flight is one thing, but when you’re talking about landing it in contested territory, it’s even harder. Aircraft typically rely upon surface radars and legacy instrument landing systems when they’re required to penetrate weather for landing. The radars and instrument landing systems emit energy that adversaries can detect, which puts aircraft and landing locations at risk.

So what do you do in that case? You use a secure encrypted data link instead. That’s the job of the Joint Precision Approach and Landing System, also known as JPALS. It goes on all three variants of the F-35, giving them a way to land on ships at sea, as well as temporary airfields in remote locations, in just about any weather. Raytheon builds the ground stations.

With JPALS, naval commanders can launch aircraft in all kinds of conditions, knowing they’ll be able to return and land once the mission is over. It also saves fuel, preventing pilots from having to loiter and refuel until landing conditions are more favorable.

“It gives them options, and it gives the pilot a sense of security, knowing they’re coming back home,” said retired U.S. Navy Rear Adm. CJ Jaynes, who now works at Raytheon as an executive technical advisor.

On land, JPALS basically gives ground forces an instant airport – it can be set up quickly and in the most austere locations, which opens up all kinds of tactical options.

“Think about special ops," Jaynes said. "You go in, you get out.”